Level of Detail

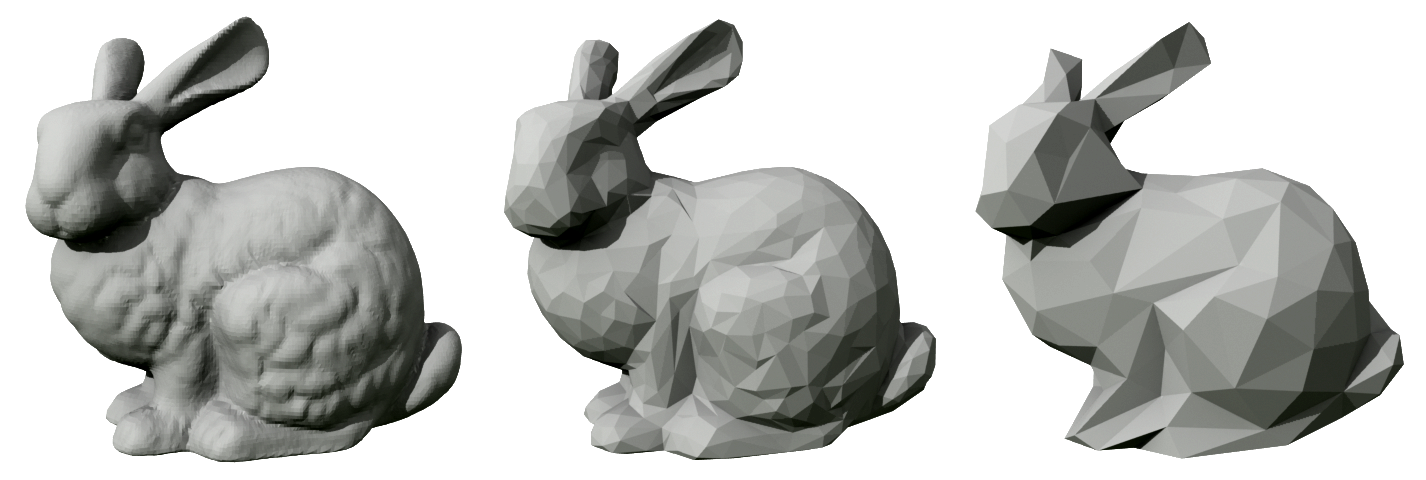

In 3D graphics, there’s a technique called Level of Detail (LoD). The idea is simple: why spend GPU cycles rendering every vertex of a distant mountain when the player can’t tell the difference between ten thousand triangles and a hundred? So the engine swaps in a lower-polygon model. As you get closer, it swaps in a higher one. Done well, the player never notices.

The algorithms have gotten wildly sophisticated over the decades. Modern engines don’t just swap between a few discrete models. They can continuously stream geometry, dissolve between levels, even procedurally generate detail on the fly. But the core insight hasn’t changed: don’t compute what nobody’s looking at.

I keep coming back to this idea because I think it describes one of the central activities of building software. Not the code part—the thinking part.

Models All the Way Down

We spend our days building and navigating models. Code is the most visible kind, but the mental models are what actually matter. When I’m debugging a production issue, I’m not holding the entire system in my head. I’m holding a low-polygon version, just enough shape to know where to look, with the ability to zoom in when something catches my eye.

Abstraction is the core operation here. When I draw a box on a whiteboard and label it “database,” I’ve loaded a low-LoD model. I know there’s a sprawling world of B-trees and query planners and buffer pools in there, but right now I don’t need those polygons. I just need to say “data goes here.” I need the silhouette.

Even the phrase “black box” is a kind of low-polygon model: a cube with no visible internals. You only need the shape of it. What goes in, what comes out.

This is something experienced engineers do instinctively. A senior engineer waves their hand and says “that part’s fine, the bug is over here.” Zoom out to understand the architecture. Zoom in to chase the bug. Zoom back out to check whether the fix makes sense. The skill isn’t knowing everything about the system. It’s knowing what resolution you need right now.

Context Windows

Here’s what’s been rattling around my head: LLMs have a version of this problem, and it’s weirdly parallel to our own.

When you work with an LLM, context is everything. Too little context and it makes dumb assumptions: it fills in the missing polygons with whatever its training data suggests, which might be completely wrong for your situation. Too much context and it gets lost: the relevant details drown in noise, the model starts contradicting itself, the reasoning goes soft.

Getting an LLM to do good work is largely a LoD problem. You need to load the right model of the situation into its context window, at the right resolution. High detail on the part you’re working on. Lower detail (but not zero) on the surrounding architecture. Maybe just a sentence about the broader system.

We do the same thing with our own brains all day long. We just never think of it that way.

Fifty Thousand Lines a Day

So here comes AI, and the geometry starts generating itself.

Adam Jacob gave a talk at CfgMgmtCamp this week where he laid it all out pretty bluntly. He’s fresh off shutting down System Initiative (six years, seven product iterations, didn’t find fit), and he’s rebuilt a prototype in three days with AI. He says people he knows and trusts are generating 50,000 lines of working code per day, single-threaded. His message to the infrastructure community: the time for skepticism is over. The velocity increase is too high. Adapt or get left behind.

His framework for what’s left for humans is design and planning. Implementation, testing, review: that’s all agent work now. “Are you reading the code? The answer is not really. Not really. I can’t. It’s going too fast.” Code principles like DRY don’t matter anymore because you’re never reading the code. The only thing that matters is software architecture: giving the agents enough structure to stay coherent.

It’s a “let it rip” vision. Crank the polygon count to maximum. The GPU can handle it now, so why hold back?

The Rigor Move

On the other end of the spectrum, the Oxide folks had a conversation recently about engineering rigor in the LLM age that lands in a very different place.

One example: Rain Paharia wrote one implementation by hand, then had the LLM replicate the pattern across four variants: 20,000 lines plus 5,000 doc tests in under a day. Without the LLM this library might never have shipped at all. The tedium-to-value ratio was just too punishing. The LLM didn’t replace the rigor. It made the rigorous version feasible.

The pattern across the whole conversation is the same: LLMs remove friction from the details, which frees you up to spend more time on the parts that actually require careful judgment. More rigor, not less. The polygon budget went up, and they’re spending it on quality rather than quantity.

Carving Back

Adam’s right that the velocity increase is real and not going away. But I think the “50,000 lines a day” framing mistakes output for progress. We’ve always known that lines of code is a terrible metric. The interesting question isn’t how much code you can generate. It’s how much code you can justify.

My hunch is that we’ll spend just as much time and energy carving code back as we will generating it. If generating code is nearly free, the scene fills up with geometry fast. But your rendering budget—working memory, attention, the ability to reason about what you’ve built—doesn’t scale the same way. And sometimes the right move isn’t a more sophisticated LoD strategy. It’s simplifying the scene itself. Delete the sprawling implementation and replace it with something you can actually reason about.

The GPU story played out the same way. GPUs are absurdly more powerful than they were twenty years ago. And the results are real: photorealistic worlds spanning kilometers, running at hundreds of frames per second. But you don’t get there by throwing the whole map at the hardware. That gets you a very pretty slideshow. You get there because graphics engineers got better at managing what to render and what to skip. Stream in the right portion of the map so the player doesn’t hit a loading screen. Drop everything outside the viewport as they look around. Cull what’s behind that wall. Photorealism is a bunch of dances with data: deciding what to load, what to keep, and what to throw away, hundreds of times per second.

The raw power didn’t eliminate the LoD problem. It moved it. The engineers aren’t hand-placing low-poly stand-ins anymore, but they’re still spending their days figuring out what the player needs to see and what they can get away with not rendering. The work changed shape, but the discipline is what delivers the fidelity.

I think that’s where we’re headed with code. The bottleneck was producing it, and that bottleneck has loosened. We’re going to build better software because of it, just like GPUs gave us better-looking games. But the pressure moves to a part of the work that’s always been there: knowing what should exist and what shouldn’t. That takes human judgment, but the same tools that can generate 50,000 lines a day might also help us figure out which 5,000 to keep.

The Constant

The tools around this activity are changing fast. I can load a low-LoD model of a subsystem I’ve never even seen by asking an LLM to summarize it. I can vaguely describe a building and get back a ream of floor plans. These are real, meaningful changes to the speed of the work. But the work itself—the deciding, the choosing, the constant question of “how much do I need to know right now?”—that part hasn’t changed at all. I don’t think it can. Somebody still has to decide what the thing should do, and somebody has to navigate what’s been built. That’s not the bottleneck. That’s the work.

A distant mountain doesn’t need every triangle. But the thing in the player’s hands, the thing they’re interacting with every single frame, needs all the polygons you can give it. No amount of GPU power changes that. The player is always looking at something.

Knowing what that something is, that’s the gig. It always has been.